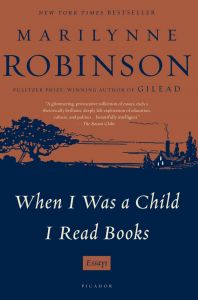

When I Was a Child I Read Books

The following is Freedom of Thought, Chapter 2 of Marilynne Robinson's book When I Was a Child I Read Books.

Over the years of writing and didactics, I accept tried to free myself of constraints I felt, limits to the range of exploration I could make, to the kind of intuition I could credit. I realized gradually that my ain religion, and religion in general, could and should disrupt these constraints, which amount to a small and narrow definition of what human beings are and how human life is to be understood. And I have often wished my students would notice religious standards nowadays in the culture that would express a real love for human life and encourage them besides to pause out of these aforementioned constraints. For the educated amongst united states, moldy theories we learned as sophomores, memorized for the test and never consciously thought of over again, exert an authorisation that would embarrass us if nosotros stopped to consider them. I was educated at a center of  behaviorist psychology and spent a certain amount of time pestering rats. There was some sort of maze-learning experiment involved in my final course, and since I remember the rat who was my colleague as uncooperative, or perhaps merely incompetent at being a rat, or tired of the whole affair, I don't think how I passed. I'm sure coercion was non involved, since this rodent and I avoided contact. Blackmail was, of course, central to the experiment and no black mark against either of us, though I must say, mine was an Eliot Ness amongst rats for its resistance to the lure of, say, Cheerios. I should probably have tried raising the stakes. The idea was, in whatever case, that behavior was conditioned past reward or its absence, and that one could extrapolate meaningfully from the straightforward demonstration of rattish self-interest promised in the literature, to the admittedly more complex question of human motivation. I have read after that a female rat is so gratified at having an infant rat come down the reward chute that she will do what ever is demanded of her until she has filled her cage with them. This seems to me to complicate the definition of self-involvement considerably, just complexity was non a concern of the behaviorism of my youth, which was reductionist in every sense of the discussion.

behaviorist psychology and spent a certain amount of time pestering rats. There was some sort of maze-learning experiment involved in my final course, and since I remember the rat who was my colleague as uncooperative, or perhaps merely incompetent at being a rat, or tired of the whole affair, I don't think how I passed. I'm sure coercion was non involved, since this rodent and I avoided contact. Blackmail was, of course, central to the experiment and no black mark against either of us, though I must say, mine was an Eliot Ness amongst rats for its resistance to the lure of, say, Cheerios. I should probably have tried raising the stakes. The idea was, in whatever case, that behavior was conditioned past reward or its absence, and that one could extrapolate meaningfully from the straightforward demonstration of rattish self-interest promised in the literature, to the admittedly more complex question of human motivation. I have read after that a female rat is so gratified at having an infant rat come down the reward chute that she will do what ever is demanded of her until she has filled her cage with them. This seems to me to complicate the definition of self-involvement considerably, just complexity was non a concern of the behaviorism of my youth, which was reductionist in every sense of the discussion.

It wasn't all behaviorism. We besides pondered Freud's argument that primordial persons, male, internalized the male parent as superego by really eating the poor fellow. Since then nosotros have all felt bad — well, the male among united states, at to the lowest degree. Whence human complication, whence civilisation. I did improve on that test. The plot was catchy.

The state of affairs of the undergraduate rarely encourages systematic incertitude. What Freud thought was of import considering it was Freud who idea it, then with B. F. Skinner and whomever else the curriculum held upwardly for our admiration. There must be something to all this, even if it has only opened the door a caste or two on a fuller understanding. Then I thought at the fourth dimension. And I likewise idea it was a very dour light that shone through that door, and I shouldered my share of the supposedly inevitable gloom that came with being a modern. In English language class we studied a poem by Robert Frost, The Oven Bird. The poem asks "what to make of a diminished thing." That diminished thing, said the instructor, was man experience in the modern world. Oh dear. Mod aesthetics. We must learn from this poem "in singing not to sing." To my undergraduate self I thought, "But what if I like to sing?" And so my philosophy professor assigned us Jonathan Edwards'southward Doctrine of Original Sin Dedicated, in which Edwards argues for "the arbitrary constitution of the universe," illustrating his point with a gorgeous footnote most moonlight that even then began to dispel the dreary determinisms I was learning elsewhere. Improbable as that may sound to those who have not read the footnote.

Marilynne Wilson Talks to Bill About Her New Book, Lila

At a certain point I decided that everything I took from studying and reading anthropology, psychology, economics, cultural history and so on did not square at all with my sense of things, and that the tendency of much of it was to posit or assume a man simplicity within a simple reality and to marginalize the sense of the sacred, the beautiful, everything in any mode lofty. I exercise not hateful to propose, and I underline this, that at that place was any sort of plot against organized religion, since religion in many instances abetted these tendencies and does even so, non least by retreating from the cultivation and commemoration of learning and of beauty, past dumbing downwards, every bit if people were less than God fabricated them and in need of nothing so much as condescension. Who among us wishes the songs we sing, the sermons we hear, were only a little dumber? People today — television — video games — diminished things. This is always the pretext.

Simultaneously, and in a fourth dimension of supposed religious revival, and among those especially inclined to feel religiously revived, we have a lodge increasingly defined by economic science and an economics increasingly reminiscent of my experience with that rat, and so-called rational-pick economic science, which assumes that nosotros volition all observe the shortest manner to the advantage, and that this is basically what we should enquire of ourselves and — this is at the center of it all — of ane another. After all these years of rational choice, brother rat might like to take a wait at the packaging just to see if there might be a little melamine in the inducements he was being offered, hoping, of course, that the vendor considered it rational to provide that kind of information. We do not deal with one another as soul to soul, and the churches are as answerable for this as anyone.

If nosotros think we have done this voiding of content for the sake of other people, those to whom we suspect God may have given a somewhat lesser brilliance than our own, we are presumptuous and also irreverent. William Tyndale, who was

burned at the stake for his translation of the Bible, who provided much of the virtually beautiful language in what is called by usa the Male monarch James Bible, wrote, he said, in the language a plowboy could sympathize. He wrote to the comprehension of the profoundly poor, those who would exist, and would have lived amidst, the utterly unlettered. And he created one of the undoubted masterpieces of the English language language. Now we seem to feel dazzler is an arrayal of some sort. And this notion is equally influential in the churches equally it is anywhere. The Bible, Christianity, should have inoculated united states against this kind of boldness for ourselves and one another. Clearly it has non.

For me, at to the lowest degree, writing consists very largely of exploring intuition. A character is really the sense of a grapheme, embodied, attired and given voice as he or she seems to require. Where does this creature come from? From watching, I suppose. From reading emotional significance in gestures and inflections, as we all practice all the fourth dimension. These moments of intuitive recognition float complimentary from their particular occasions and recombine themselves into not-existent people the writer and, if all goes well, the reader feel they know.

Words similar "sympathy," "empathy" and "compassion" are overworked and overcharged — in that location is no give-and-take for the experience of seeing an cover at a subway stop or hearing an argument at the next tabular array in a restaurant.

There is a great difference, in fiction and in life, between knowing someone and knowing about someone. When a author knows almost his graphic symbol he is writing for plot. When he knows his graphic symbol he is writing to explore, to feel reality on a fix of nerves somehow non quite his own. Words like "sympathy," "empathy" and "pity" are overworked and overcharged—there is no word for the experience of seeing an embrace at a subway finish or hearing an argument at the next table in a restaurant. Every such instant has its own emotional coloration, which retentivity retains or heightens, and and then the most sidelong, unintended moment becomes a part of what we have seen of the globe. And then, I suppose, these moments, equally they have seemed to us, constellate themselves into something a little like a spirit, a piffling like a human presence in its mystery and distinctiveness.

Two questions I can't really answer about fiction are (1) where it comes from, and (2) why we need information technology. But that we do create information technology and besides crave it is beyond dispute. In that location is a tendency, considered highly rational, to reason from a narrow ready of interests, say survival and procreation, which are supposed to govern our lives, and then to care for everything that does not fit this model as anomalous clutter, extraneous to what we are and probably best done without. But all we really know virtually what we are is what we do. At that place is a trend to fit a tight and bad-mannered carapace of definition over humankind, and to effort to trim the living creature to fit the dead shell. The advice I give my students is the same advice I give myself — forget definition, forget assumption, sentry. Nosotros inhabit, nosotros are part of, a reality for which explanation is much too poor and pocket-size. No physicist would dispute this, though he or she might be less ready than I am to have recourse to the quondam language and phone call reality miraculous. By my lights, fiction that does not acknowledge this at to the lowest degree tacitly is non truthful. Why is it possible to speak of fiction as truthful or imitation? I have no idea. But if a fourth dimension comes when I seem not to be making the stardom with some degree of reliability in my own piece of work, I hope someone will be kind enough to permit me know. When I write fiction, I suppose my attempt is to simulate the integrative work of a listen perceiving and reflecting, drawing upon culture, retention, censor, conventionalities or assumption, circumstance, fear and want — a mind shaping the moment of experience and response and then reshaping them both as narrative, holding 1 thought against another for the upshot of analogousness or contrast, evaluating and rationalizing, feeling compassion, taking criminal offence. These things practise happen simultaneously, after all. None of them is agile by itself, and none of them is determinative, because there is that mysterious affair the cognitive scientists call self-awareness, the human ability to consider and appraise i's ain thoughts. I suspect this self-sensation is what people used to telephone call the soul.

Modern discourse is non actually comfortable with the word "soul," and in my opinion the loss of the word has been disabling, not only to religion just to literature and political thought and to every humane pursuit.

Modern soapbox is not actually comfy with the word "soul," and in my opinion the loss of the word has been disabling, not just to religion just to literature and political thought and to every humane pursuit. In gimmicky religious circles, souls, if they are mentioned at all, tend to be spoken of as saved or lost, having answered some set of divine expectations or failed to answer them, having arrived at some crucial realization or failed to make it at it. So the soul, the masterpiece of creation, is more or less reduced to a token signifying cosmic acceptance or rejection, having petty or nil to do with that miraculous matter, the felt experience of life, except insofar every bit life offers distractions or temptations.

Having read recently that at that place are more neurons in the human brain than at that place are stars in the Milky Way, and having read whatever number of times that the human encephalon is the nearly circuitous object known to exist in the universe, and that the mind is non identical with the brain but is more mysterious nevertheless, it seems to me this amazing nexus of the self, so uniquely elegant and capable, merits a name that would signal a difference in kind from the ontological run of things, and for my purposes "soul" would practice nicely. Perhaps I should pause here to clarify my meaning, since at that place are those who feel that the spiritual is diminished or denied when it is associated with the physical. I am non amongst them. In his Alphabetic character to the Romans, Paul says, "Ever since the creation of the globe [God'due south] invisible nature, namely, his eternal power and deity, has been conspicuously perceived in the things that have been made." If nosotros are to consider the heavens, how much more than are we to consider the magnificent energies of consciousness that make whomever we pass on the street a far grander marvel than our galaxy? At this point of dynamic convergence, telephone call it self or phone call information technology soul, questions of right and incorrect are weighed, love is felt, guilt and loss are suffered. And, over time, germination occurs, for weal or woe, governed in large role by that unaccountable capacity for selfawareness.

The locus of the man mystery is perception of this world. From it proceeds every thought, every art. I like Calvin's metaphor — nature is a shining garment in which God is revealed and concealed. As nosotros perceive we interpret, and we make hypotheses. Something is happening, it has a certain character or meaning which nosotros usually experience we understand at to the lowest degree tentatively, though experience is almost ever available to reinterpretations based on subsequent feel or reflection. Here occurs the weighing of moral and ethical selection. Behavior proceeds from all this, and is interesting, to my mind, in the degree that it tin can be understood to proceed from it. Nosotros are much afflicted now by dull, fruitless controversy. Very ofttimes, perchance typically, the about important aspect of a controversy is not the area of disagreement but the hardening of agreement, the tacit granting on all sides of assumptions that ought non to be granted on whatever side. The treatment of the concrete as a distinct category antithetical to the spiritual is 1 instance. There is a securely rooted notion that the fabric exists in opposition to the spiritual, precludes or repels or trumps the sacred as an idea. This dichotomy goes back at to the lowest degree to the dualism of the Manichees, who believed the physical world was the cosmos of an evil god in perpetual conflict with a good god, and to related teachings within Christianity that encouraged mortification of the flesh, renunciation of the world and and so on.

The assumption persists amid us nevertheless, vigorous every bit ever, that if a thing tin can be "explained," associated with a physical procedure, information technology has been excluded from the category of the spiritual.

For virtually equally long as there has been science in the West there has been a pregnant strain in scientific thought which assumed that the physical and material forestall the spiritual. The assumption persists amongst us notwithstanding, vigorous as ever, that if a thing can exist "explained," associated with a physical process, it has been excluded from the category of the spiritual. But the "physical" in this sense is simply a disappearingly thin slice of being, selected, for our purposes, out of the totality of beingness by the fact that we perceive it as solid, substantial. We all know that if we were the size of atoms, chairs and tables would appear to us equally loose clouds of energy. Information technology seems to me very amazing that the arbitrarily selected "physical" world we inhabit is coherent and lawful. An older vocabulary would offering the word "miraculous." Knowing what we know now, an earlier generation might see divine providence in the fact of a globe coherent enough to be experienced past us as complete in itself, and as a basis upon which all claims to reality tin can be tested. A truly theological age would see in this divine Providence intent on making a human habitation within the wild roar of the cosmos.

Just almost anybody, for generations now, has insisted on a precipitous stardom betwixt the concrete and the spiritual. So we have had theologies that actually proposed a "God of the gaps," equally if God were not manifest in the cosmos, equally the Bible is then inclined to insist, only instead survives in those nighttime places, those black boxes, where the light of science has not nevertheless shone. And we take atheisms and agnosticisms that make precisely the same argument, only assuming that at some fourth dimension the light of scientific discipline will indeed dispel the last shadow in which the holy might have been thought to linger. Religious feel is said to be associated with activity in a particular part of the brain. For some reason this is supposed to imply that it is delusional. Merely all idea and feel can exist located in some function of the brain, that encephalon more replete than the starry heaven God showed to Abraham, and we are non in the habit of assuming that it is all delusional on these grounds. Zippo could justify this reasoning, which many religious people take as seriously as whatsoever atheist could do, except the idea that the concrete and the spiritual cannot abide together, that they cannot be one impunity. We live in a time when many religious people experience fiercely threatened by science. O ye of lilliputian faith. Let them subscribe to Scientific American for a yr and then tell me if their sense of the grandeur of God is not profoundly enlarged past what they take learned from it. Of grade many of the articles reflect the assumption at the root of many problems, that an account, however tentative, of some structure of the cosmos or some transaction of the nervous system successfully claims that part of reality for secularism. Those who encourage a fear of science are really saying the same thing. If the onetime, untenable dualism is put bated, nosotros are instructed in the countless brilliance of creation. Surely to do this is a privilege of modern life for which we should all be grateful.

For years I have been interested in ancient literature and religion. If they are non ane and the same, certainly neither is imaginable without the other. Indeed, literature and religion seem to take come into being together, if by literature I can be understood to include pre-literature, narrative whose purpose is to put homo life, causality and meaning in relation, to brand each of them in some degree intelligible in terms of the other 2. I was taught, more or less, that we moderns had discovered other religions with narratives resembling our ain, and that this discovery had brought all faith down to the level of anthropology. Sky gods and globe gods presiding over survival and procreation. Humankind pushing a lever in the hope of aperiodic reward in the form of pelting or victory in the side by side tribal skirmish. From a very simple understanding of what organized religion has been we tin extrapolate to what religion is now and is intrinsically, so the theory goes. This design, of proceeding from presumed simplicity to a degree of elaboration that never loses the primary character of simplicity, is strongly recurrent in modern thought.

I think much religious thought has as well been intimidated by this supposed discovery, which is odd, since information technology certainly was not news to Paul, or Augustine, or Thomas Aquinas or Calvin. All of them quote the pagans with adoration. Possibly but in Europe was ane form of religion ever and then dominant that the fact of other forms could institute any sort of trouble. There has been an influential modern tendency to make a sort of slurry of religious narratives, asserting the discovery of universals that don't actually exist among them. Mircea Eliade is a prominent instance. And in that location is Joseph Campbell. My primary criticism of this kind of scholarship is that it does non bear scrutiny. A secondary criticism I would offer is that it erases all evidence that organized religion has, anywhere and in any form, expressed or stimulated thought. In any case, the anthropological bias among these writers, which may get in seem free of all parochialism, is in fact absolutely Western, since information technology regards all religion as man beings interim out their nature and no more than that, though I admit there is a gauziness virtually this worldview to which I will not attempt to do justice hither.

This is the anthropologists' reply to the question, why are people virtually always, virtually everywhere, religious. Another answer, favored by those who merits to be defenders of science, is that religion formed around the desire to explicate what prescientific humankind could not account for. Once again, this notion does not deport scrutiny. The literatures of antiquity are clearly about other business organisation.

Some of these narratives are then ancient that they clearly existed before writing, though no doubt in the forms nosotros have them they were modifi ed in being written down. Their importance in the development of human being culture cannot be overstated. In artifact people lived in complex city- states, carried out the work and planning required by primitive agriculture, built ships and navigated at great distances, traded, made law, waged state of war and kept the records of their dynasties. But the one affair that seems to have predominated, to have laid out their cities and filled them with temples and monuments, to have established their identities and their cultural boundaries, to have governed their calendars and enthroned their kings, were the vivid, atemporal stories they told themselves about the gods, the gods in relation to humankind, to their city, to themselves.

I suppose it was in the 18th century of our era that the notion became solidly fixed in the Western mind that all this narrative was an endeavour at explaining what science would one solar day explain truly and finally. Phoebus drives his chariot across the sky, and so the sun rises and sets. Marduk slays the sea monster Tiamat, who weeps, whence the Tigris and the Euphrates. It is true that in some cases physical reality is accounted for, or at least described, in the terms of these myths. Simply the beauty of the myths is not deemed for by this theory, nor is the fact that, in literary forms, they had a concord on the imaginations of the populations that embraced them which expressed itself again as beauty. Over fourth dimension these narratives had at least as profound an effect on architecture and the visual arts as they did on literature. Anecdotes from them were painted and sculpted everywhere, even on house concur goods, vases and drinking cups.

This kind of imaginative engagement bears no resemblance what ever to an assimilation of explanatory models by these civilizations. Maybe the tendency to think of classical religion as an attempt at explaining a world otherwise incomprehensible to them encourages united states to forget how sophisticated ancient people actually were. They were inevitably as immersed in the realm of the practical as we are. It is strangely easy to forget that they were capable of complex engineering, though and so many of their monuments however stand. The Babylonians used quadratic equations.

Yet in many instances ancient people seem to have obscured highly available real- world accounts of things. A sculptor would take an oath that the gods had fabricated an idol, afterward he himself had fabricated it. The gods were credited with walls and ziggurats, when cities themselves congenital them. Structures of enormous shaped stones went up in broad daylight in ancient cities, the walls built around the Temple by Herod in Roman-occupied Jerusalem being one case. The ancients knew, though we don't know, how this was done, evidently. But they left no account of it. This very remarkable evasion of the law of gravity was seemingly not of neat interest to them. It was the gods themselves who walled in Troy.

In Virgil's Aeneid, in which the poet in outcome interprets the ancient Greek epic tradition by attempting to renew it in the Latin linguistic communication and for Roman purposes, there is i especially famous moment. The hero, Aeneas, a Trojan who has escaped the destruction of his city, sees a painting in Carthage of the war at Troy and is deeply moved past information technology and by what it evokes, the lacrimae rerum, the tears in things. This moment certainly refers to the place in classical civilization of fine art that pondered and interpreted the Homeric narratives, which were the basis of Greek and Roman organized religion. My point hither is simply that infidel myth, which the Bible in various means acknowledges as analogous to biblical narrative despite grave defects, is not a naive attempt at science.

It is true that near a millennium separated Homer and Virgil. Information technology is besides true that through those centuries the classical civilizations had explored and interpreted their myths continuously. Aeschylus, Sophocles, and Euripides would surely have agreed with Virgil'due south Aeneas that the epics and the stories that surround them and menses from them are indeed about lacrimae rerum, about a swell sadness that pervades human life. The Babylonian Epic of Gilgamesh is about the inevitability of death and loss. This is not the kind of language, nor is it the kind of preoccupation, one would detect in a tradition of narrative that had whatever significant interest in explaining how the leopard got his spots.

The notion that religion is intrinsically a rough explanatory strategy that should exist dispelled and supplanted past science is based on a highly selective or tendentious reading of the literatures of religion.

The notion that religion is intrinsically a crude explanatory strategy that should be dispelled and supplanted past science is based on a highly selective or tendentious reading of the literatures of religion. In some cases it is certainly fair to conclude that it is based on no reading of them at all. Exist that as it may, the effect of this thought, which is very broadly causeless to be true, is over again to reinforce the notion that science and religion are struggling for possession of a single slice of turf, and scientific discipline holds the high footing and gets to choose the weapons. In fact at that place is no moment in which, no perspective from which, science equally scientific discipline can regard human life and say that in that location is a beautiful, terrible mystery in it all, a bully pathos. Fine art, music and faith tell united states that. And what they tell u.s. is true, not after the fashion of a magisterium that is legitimate only so long as it does not overlap the autonomous republic of scientific discipline. It is true considering it takes account of the universal variable, man nature, which shapes everything it touches, science equally surely and profoundly as anything else. And it is true in the tentative, suggestive, clashing, self-contradictory fashion of the testimony of a hundred one thousand witnesses, who might, taken all together, hold on no more than the shared sense that something of great moment has happened, is happening, will happen, here and amidst u.s.a..

I hasten to add together that science is a smashing contributor to what is cute and also terrible in human being. For example, I am deeply grateful to take lived in the era of catholic exploration. I am thrilled past those photographs of deep space, as many of u.s.a. are. Still, if it is true, as they are saying now, that bacteria render from space a bully deal more virulent than they were when they entered it, it is not hard to imagine that some regrettable outcome might follow our sending people to tinker effectually up there. One article noted that a man existence is full of leaner, and there is nothing to be done almost it.

Scientific discipline might note with great care and precision how a new pathology emerged through this wholly unforeseen touch on of space on our biosphere, but it could not, scientifically, absorb the fact of information technology and the origin of it into whatsoever larger frame of significant. Scientists might mention the police of unintended consequences — mention it softly, because that would sound a little brassy in the circumstances. But faith would recognize in it what religion has always known, that there is a mystery in human nature and in human being assertions of luminescence and intention, a recoil the Greeks would have called irony and attributed to some angry whim of the gods, to exist interpreted as a rebuke of human being pride if it could be interpreted at all. Christian theology has spoken of human limitation, fallen-ness, an individually and collectively disastrous bias toward fault. I call back we all know that the earth might be reaching the end of its tolerance for our presumptions. We all know we might at whatsoever time feel the force of unintended consequences, many times compounded. Scientific discipline has no language to business relationship for the fact that it may well overwhelm itself, and more and more stand helpless before its ain furnishings.

Of form science must not be judged by the claims certain of its proponents have made for it. It is not in fact a standard of reasonableness or truth or objectivity. It is human being, and has ever been 1 strategy among others in the more than general project of human self-awareness and self-assertion. Our problem with ourselves, which is much larger and vastly older than scientific discipline, has past no ways gone into abeyance since nosotros learned to brand penicillin or to split the cantlet. If antibiotics accept been used without sufficient care and have pushed the evolution of bacteria beyond the reach of their own effectiveness, if nuclear fission has become a threat to us all in the insidious form of a disgruntled stranger with a suitcase, a rebuke to every illusion of safety nosotros entertained under fine names like Strategic Defense Initiative, quondam Homer might say, "the will of Zeus was moving toward its end." Shakespeare might say, "There is a destiny that shapes our ends, rough- hew them how nosotros volition."

The tendency of the schools of idea that have claimed to exist virtually impressed by science has been to deny the legitimacy of the kind of statement it cannot make, the kind of exploration it cannot brand. And yet science itself has been profoundly shaped by that larger bias toward irony, toward error, which has been the subject of religious idea since the emergence of the stories in Genesis that tell us we were given a lavishly beautiful world and are somehow, by our nature, complicit in its decline, its ruin. Science cannot recall analogically, though this kind of thinking is very useful for making sense and significant out of the tumult of human affairs.

Nosotros take given ourselves many lessons in the perils of beingness half right, even so I dubiousness we have learned a thing. Sophocles could tell the states about this, or the Book of Job. We all know about hubris. Nosotros know that pride goeth earlier a fall. The problem is that we don't recognize pride or hubris in ourselves, any more than Oedipus did, any more than Job's and so- called comforters. Information technology tin can exist then innocuous- seeming a thing as confidence that one is right, is competent, is clairvoyant, or confidence that one is pious or pure in one's motives. As the disciples said, "Who then can be saved?" Jesus replied, "With men this is impossible, but with God all things are possible," in this instance speaking of the salvation of the pious rich. It is his consequent teaching that the comfortable, the confident, the pious stand up in special need of the intervention of grace. Mayhap this is truthful because they are most vulnerable to error — like the young rich homo who makes the astonishing decision to plow his back on Jesus'due south invitation to follow him, therefore on the salvation he sought — although there is another plow in the story, and nosotros learn that Jesus will not condemn him. I suspect Jesus should be thought of as smiling at the irony of the young human's self-defeat — from which, since he is Jesus, he is also ready to rescue him ultimately. The Christian narrative tells usa that we individually and nosotros as a globe plough our backs on what is true, essential, wholly to be desired. And it tells us that we can both know this about ourselves and forgive information technology in ourselves and 1 another, inside the limits of our mortal capacities. To recognize our bias toward error should teach us modesty and reflection, and to forgive it should assistance u.s.a. avert the inhumanity of thinking we ourselves are not as fallible as those who, in any instance, seem most at fault. Science tin give u.s.a. cognition, just it cannot give usa wisdom. Nor can religion, until it puts aside nonsense and lark and becomes itself once again.

Excerpted from When I Was a Child I Read Books by Marilynne Robinson, published in 2012 past Farrar, Straus and Giroux, LLC. Copyright (c) 2012 by Marilynne Robinson. All rights reserved.

mayfieldwasonever.blogspot.com

Source: https://billmoyers.com/2014/10/19/child-read-books/

0 Response to "When I Was a Child I Read Books"

Post a Comment